Unearthing What Archaeologists Can and Cannot Know

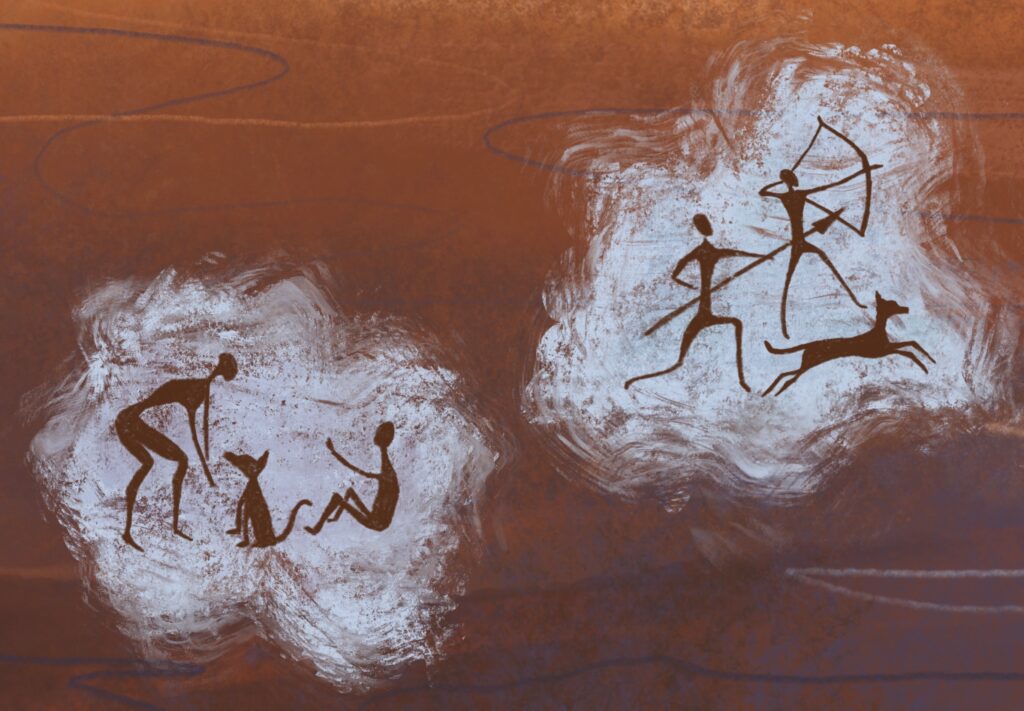

WITH STEADY HANDS, a crouching archaeologist brushes away centuries of soil, revealing the curved edge of a human skull. As they excavate deeper, the slender bones of a dog emerge. The archaeologist pauses, scanning the stillness of this shared grave.

The bones offer the illusion of a story—a villager and his beloved pet, a warrior with her guard dog, or a dog deposited as a spiritual guide in the afterlife. Or perhaps, something this archaeologist has never encountered or read about in their own narrow world.

Archaeologists are tasked with reconstructing the lives and deaths of beings who lived hundreds or thousands of years ago. They search for meaning by examining the arrangement of remains, signs of wear and tear, degraded biomolecules, and other lines of evidence. Even with this arsenal of cutting-edge methods, the past rarely speaks clearly.

When questions about these beings reach into the realm of motivations, beliefs, and identity, what can we know? How much can science say, and when must imagination take over?

As a student using bones and ancient genomes to probe past lives, I’ve been grappling with these questions about the limits of knowledge—especially as I investigate the phenomenon of dogs and humans buried together about 1,000 years ago in Europe’s Baltic region.

As I’ve come to see it, scientists must walk a fine line between silence and sensationalism when they share their conclusions with society. Archaeologists, in particular, should create space for both evidence and imagination, which may open a door to alternate worlds—such as one in which a dog’s meaning transcends your conceptions.

RETHINKING NONHUMAN LIVES

(Non-human) animals in burials are not often considered meaningful in their own right. Even when animals appear in striking burial contexts—dogs curled in graves, mummified cats, horses laid to rest in tombs—their stories are often told secondhand. Usually, the focus is on an animal’s role in human society, with possibilities drawn from archaeologists’ own experiences and worldviews. Wild animals, if recognized at all, are chalked up to ritual or myth. Domesticated horses are seen as transport tools or status symbols. Dogs have often been relegated to the role of servile companion.

Read more from the archives: “The Macabre and Magical Human-Canine Story.”

At best, these conclusions may be uncritical assumptions; at worst, they reinforce “Western” and colonial ontologies that presume other societies share transactional relationships with animals.

One striking example comes from a roughly 1,000-year-old Hopewell mound in what is now Illinois, originally excavated in the 1970s and ’80s. Within the mound, archaeologists unearthed a grave containing an animal skeleton with a string of shell beads around its neck.

Based on its size and shape, the animal was long assumed to be a puppy. The adornment and care shown in its burial led archaeologists to assume the animal was a beloved companion, domesticated and kept by humans. The conclusion made sense from the perspective of many researchers in North America, where people now buy specialty treats and hand-knit sweaters for their pups.

But when the bones were reanalyzed in 2015 by archaeologist Angela Perri and colleagues, they realized the creature was no canine: The grave belonged to a young bobcat.

Burial with intention, with beads and a dedicated grave, doesn’t always signal a domesticated creature—wild animals could also be given elaborate, careful graves.

We researchers today cannot know exactly what the bobcat meant to those who buried it. But we can say the animal meant something. Someone chose to wrap its body, adorn it, and lay it to rest in the ground.

To move beyond conclusions drawn from the world one knows, researchers must look at human-animal relationships more broadly. At Oxford, the Palaeogenomics and Bio-Archaeology Research Network (PalaeoBARN), led by Greger Larson, investigates how animals have moved, bred, and lived alongside humans. One branch of this work, led by researcher AB Siegenthaler, reexamines animal burials that fall outside familiar categories of pets and livestock, considering dogs, snakes, birds, pumas, and cases like the Hopewell bobcat. These burials suggest relationships that resist explanations of utility, ritual, or ownership.

DOGS IN IRON AGE BALTICS

My work with Oxford’s PalaeoBARN, in collaboration with researcher Eduards Plankājs at the University of Latvia, turns a similarly careful eye to roughly 1,000-year-old Iron Age cemeteries where humans and dogs were buried together. In grave after grave of different Iron Age tribes in modern-day Estonia and Latvia, canine skeletons were placed beside human ones, sometimes fully intact, sometimes curled close, sometimes resting at a person’s feet.

To understand the lives behind these burials, our team draws on multiple lines of evidence. We analyze ancient DNA to determine whether the dogs belonged to local lineages or came from elsewhere, tracing patterns of ancestry and migration. We measure chemical isotopes preserved in their bones to answer questions of diet and mobility: Did these animals eat like the people they were buried beside? Did they travel together? And we study their skeletal wear and healing to see how their bodies responded to labor, injury, and age.

Each method offers a window into the experiences of a past creature. Together, these data build a more complete understanding of not just why these dogs were buried with humans, but also how these dogs lived with humans.

Nevertheless, even with all these biological and biomolecular data, there remain many possible narratives produced—or also limited—by archaeologists’ own worldviews or drawn from ethnographic examples. The dogs may have been symbols of status, their bodies placed in the graves of elites with the same intention as a finely worked blade or imported vase. Perhaps the canines were revered as spiritual guardians, buried to protect and guide a community.

Or I might imagine a man and a dog with more closely entangled lives. They shared food and played. The dog slept at the foot of the man’s bed. They grew old together. Upon their deaths, someone made the decision to bury the man and dog as they had lived, side by side.

THE STORIES WE TELL

Whether we imagine status symbols, spiritual guardians, or lifelong companions, each interpretation rests on the same fragments of evidence. Scientific techniques provide archaeologists with increasingly powerful tools for illuminating the past, but there is an often-unrecognized malleability in our interpretations.

It might seem that portraying scientific knowledge as fixed and authoritative would be productive, especially in the current climate of antiscience rhetoric in the U.S., where government agencies are pulling out of the World Health Organization, promoting vaccine skepticism, and denying health care to transgender youth, to name a few examples.

In such a context, it is tempting for researchers to dig our heels in regarding the authority of scientific “truth.” But the misuse of science is not remedied by treating it as unimpeachable.

Rather, this rigidity feeds an also insidious belief that science speaks with a singular and final voice, delivering truth that is fixed, unquestionable, and objective. This perception misrepresents science and undermines its very strength. As written by professor of science education Jonathan Osborne and colleagues for Scientific American, “When we don’t learn the nature of consensus, how science tends to be self-correcting and how community as well as individual incentives bring to light discrepancies in theory and data, we are vulnerable to false beliefs and antiscience propaganda.”

In archaeology, the issue of how to present scientific practices and theories is especially pressing. Weighty interpretations of ancestry, identity, and belonging often circulate far beyond academic spaces, shaping public memory, political narratives, and cultural self-understanding. We do not have to look far to find the misuse of such narratives: to bolster scientific racism, as a weapon to rationalize violent settler-colonialism, and to reinforce false dichotomies that wrongly situate Indigenous knowledge in opposition to archaeological or “scientific” knowledge.

Ambiguity in archaeology and science might seem unsettling, particularly to students and researchers who want to cling to “fact” as a buoy in uncertain waters. But I choose to embrace ambiguity as generative.

My team’s ongoing DNA analyses, for example, could reveal genetic relations between dogs buried in different graves. But the social relations between canines and humans sharing those graves cannot be definitively resolved by these analyses. The same data could explain the dogs as beloved companions, prized status symbols, or something else altogether. In considering the possibilities, I should push myself beyond hypotheses drawn from my narrow worldview. This is where our imaginations as archaeologists must step in.

What archaeology requires of researchers is thoughtful engagement with the stories we tell about the dead, about the past, about ourselves.

What archaeology asks of everyone is an openness to alternate worlds. An understanding that your society, with its ways of working, worshipping, learning, loving—even knowing a dog—is just one permutation of endless human and beyond human possibilities.