Do Africa’s Mass Animal Migrations Extend Into Deep Time?

Hundreds of hooves thunder, announcing the herd’s approach. A cloud of dust rolls closer. The low mooing of wildebeest is within earshot.

Every year, when the seasons change in Eastern Africa, millions of large herbivores journey to find food and water. Along the way, zebras, gazelles, elephants, and other animal icons evade predators, cross treacherous rivers, and risk deadly diseases. The largest of these mass migrations, a 300-mile loop across Kenya and Tanzania, has been nicknamed the greatest spectacle on Earth.

Witnessing this grandiose scene, it may feel like the animals and their ancestors have been undertaking these migrations since time immemorial. For me, an archaeologist, it’s easy to imagine ancient foragers there, too, traveling long distances to hunt the animals.

I’m not alone: For decades, archaeologists have believed that these seasonal migrations—of herbivores and humans pursuing them—extended back to at least the last ice age’s peak, some 20,000 years ago.

But over the last decade or so, new research on food scraps from archaeological sites and chemical signatures in fossil teeth challenge this story. It seems past hunter-gatherers traveled less than we archaeologists thought. Many groups hunted a broader variety of nonmigratory animals close to their camps.

As for the iconic migrating herds, we are also beginning to think that many of these seasonal journeys only started within the last 10,000 years. Migratory behavior may come and go throughout the deep history of an animal species. That means conservation efforts should not just focus on preserving routes existing today but also understand the ecological conditions that spur or deter spectacular migrations.

PAST AND PRESENT FORAGERS

Members of our species, Homo sapiens, have been hunting and gathering since our kind appeared in Africa around 300,000 years ago. Other means of obtaining food—pastoralism, farming, agriculture—only emerged in some places about 10,000 years ago, and in most corners of Earth much later.

For clues about how our ancestors lived for most of our history, archaeologists observe contemporary groups that mainly eat wild plants and animals. Of course, these modern foragers live differently than their spear-wielding predecessors: Historical and contemporary hunter-gatherer societies exchange food with non-foragers, and some hunt with modern weapons such as guns. The type and abundance of animals today are also different compared to the past.

Knowing the limits of what present-day foragers can reveal about past ones, researchers turn to the archaeological traces left by ancient humans and the animals they lived alongside.

In 2019, when I began my doctoral research examining animal teeth from the last 25,000 years, I imagined the creatures were seasonal migrators regularly hunted by nomadic foragers. After all, textbook thinking in my field professes that it wasn’t until much later, with the adoption of agriculture and pastoralism, that humans could “settle down” in one place.

But as I reviewed earlier research, I soon realized there was no evidence large herbivores of Africa’s past were migrating long distances.

To tackle the question, I turned to clues embedded in bygone animals’ teeth.

MIGRATIONS ETCHED IN TEETH

Bzzzzzzzz.

A drill tip carves a straight groove into the outer enamel of a fossil tooth. White powder rains onto a carefully placed square of paper. I collect the dust in a plastic vial and move on to the next groove, parallel to the first. Then I repeat a few hundred times.

I’m collecting the powder to analyze isotopes, atoms that belong to the same element but have different weights. Since isotopes were first discovered in the 1910s by British chemist Frederick Soddy, scientists have identified a couple hundred naturally occurring isotopes across the Periodic Table of Elements.

Since the 1970s, scientists have been measuring certain isotopes in bones and teeth to glean information about long-gone creatures (including humans). Because the masses differ, isotopes move through chemical reactions with differing speed and ease. As a result, the ratios of heavy to light isotopes in bones and teeth can reflect aspects of an animal’s life—depending on which element is probed and the reactions it went through. Oxygen hints at how rainy an animal’s environment was. Carbon provides clues about the proportion of different plants in its diet.

And strontium—my target this day in the lab—offers insights about the animal’s travels.

Animals ingest strontium through water and food, recording in their bodies the characteristic “chemical signature” of a certain place. By repeating this analysis in portions of the teeth that formed at different times of the year, I can reconstruct the seasonal movements of animals from thousands of years ago.

I pour lab-grade bleach in the vials to destroy organic molecules. The enamel’s inorganic mineral is what I want. Next, I introduce acetic acid, which eats recently formed mineral and leaves the old stuff. The vials are loaded into a mass spectrometer, an instrument that can measure various isotopes.

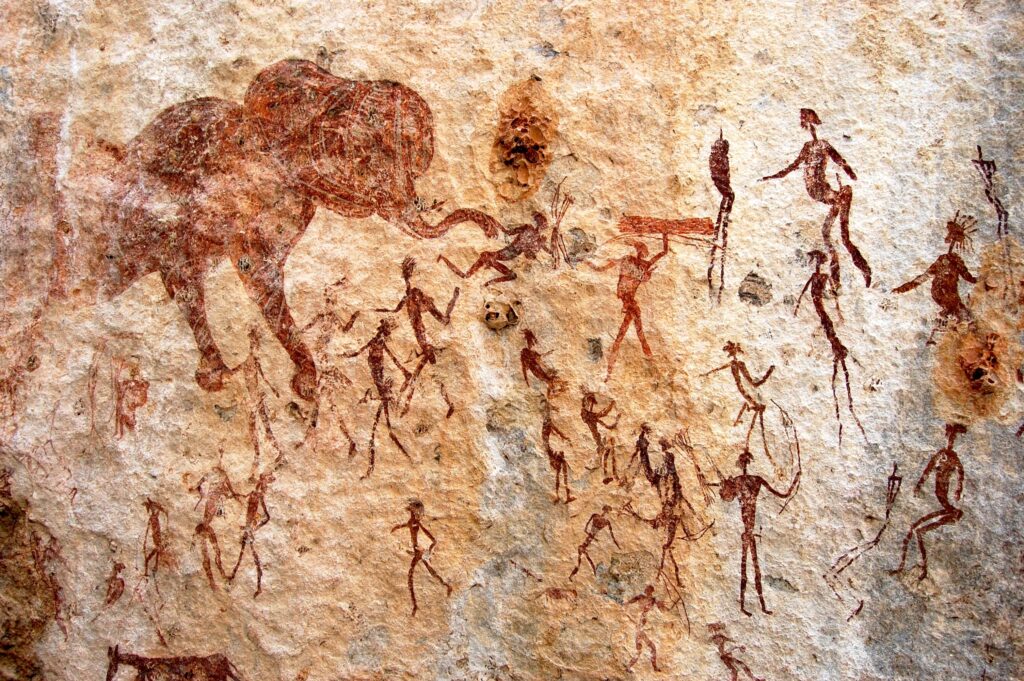

The teeth belonged to zebra and wildebeest that lived between 10,000 and 20,000 years ago in Eastern Africa and were hunted by ancient foragers. As part of a team led by my graduate adviser Jessica Thompson, I helped excavate the fossils from archaeological sites in Malawi’s Kasitu Valley. The broad valley is peppered with granite hills, some of which bear unmistakable signs of ancient human presence: painted rock art and scatters of stone objects.

Today zebra and wildebeest migrate tens to hundreds of miles in several regions of Africa. I expected to learn from the strontium isotopes that the ancient animals also migrated seasonally—and presumably were trailed by equally mobile hunter-gatherers.

But the isotope values did not change much across each tooth. It seems the animals stayed put year-round near the sites where we found their fossilized remains.

Ditto for the humans: Our team also recovered ancient DNA from three adults and two infants who inhabited one of the sites between 16,000 and 8,000 years ago. The DNA showed that people lived in the same region for thousands of years and were closely related to neighbors, sometimes located only a few tens of miles away.

RETHINKING ROVING PEOPLE AND PREY

This surprising lack of animal wanderlust is not unique to our team’s sites in Malawi. Using the same chemical techniques, other researchers also did not find proof of migratory animals where they were expecting them. These include the ancient Serengeti near Lake Victoria and the Paleo-Agulhas Plain, a lost stretch of land off the southern coast of South Africa that today is submerged.

If these mass migrations are a recent phenomenon, what are the implications for conservation?

If large social herbivores mostly stayed in the same area year-round, their numbers were likely small; otherwise, they would have run out of food. These thin herds may not have been enough to support hunter-gatherer communities, which likely supplemented their big game hauls with plenty of smaller prey and plant foods. This seems to be how Pleistocene communities diversified their diets in places as far apart as today’s Greece, Germany, South Africa, and others.

Back to Malawi, my study of over 10,000 animal remains revealed that people indeed had a broad menu, including plenty of smaller herbivores, rabbits, and even monkeys. Furthermore, when contemporary hunter-gatherers carry prey for long distances, they often select only the meatiest parts. But in these sites, most animal parts are present, suggesting that transport distances were short.

If these mass migrations are a recent phenomenon, what are the implications for conservation?

LESSONS FOR CONSERVATION

Many migratory routes in Africa have been disrupted by herding and veterinary fences put up to separate wild animals from their domestic counterparts. Conservationists understandably urge us to protect the remaining migrations.

But results from archaeological research reframe the issue: Are some mass migrations themselves a consequence of human encroachment in the habitat of these animals? Or perhaps some complex combination of climatic and biological factors?

Maybe my team just happened to study individual animals or communities that did not migrate in the past—renegades from what most creatures were doing back then. After all, today not all zebra and wildebeest migrate. But the mounting evidence for ancient animals and foragers staying put indicates we have more to learn about ecosystems—their history and their future.

Watching the wildebeest storm by today, we can marvel at the momentary spectacle and wonder whether their footsteps are echoed in deep time.