The Tomb That Told of a Women’s Kingdom

A TOMB IN THE HIGHLANDS

In 2005, a truck rumbled down a dirt road in western Tibet, its heavy wheels collapsing ground as it passed. When monks came to clear the debris, they found fragments of a wooden coffin, human bones, and traces of silk.

The accident revealed a tomb beneath the road and a doorway into a forgotten world.

Nearly a decade later, archaeologists returned to excavate the site now known as Gurugyam (གུ་རུ་གྱམ།) Cemetery. Among the many stone-lined burial chambers, one tomb stood out: M2—named using a common convention in Chinese archaeology, where M stands for mu (墓), meaning “tomb,” and the number marks its order of discovery.

The tomb was unusually large and intricately constructed. Whatever precious objects may have once filled it had long disappeared. But the tomb still held scattered bones from what appeared to be a female person—a conclusion later confirmed by ancient DNA analysis.

Who was she? Initially, researchers cast the person in M2 as a sacrificed attendant, assuming a woman would not receive such distinguished burial quarters—an idea more rooted in present-day biases than circumstances of the past. But in the near decade since she surfaced, accumulating evidence suggests the individual was a high-status woman, perhaps a political leader.

And her existence may signal the reality of a place normally described in legends: the “Women’s Kingdom” (女国 Nüguo), written about in 7th- to 8th-century Chinese texts.

I did not meet M2’s occupant in the dust of excavation but on the pages of a research report. As an archaeologist interested in gender and power, I found myself repeatedly returning to her life and her afterlife as the subject of scientific inquiry. I began to glimpse this ancient world where women held power. At the same time, I wondered why her story remains relegated to footnotes of scientific studies, buried in another sense.

TRACES OF A WOMEN’S KINGDOM

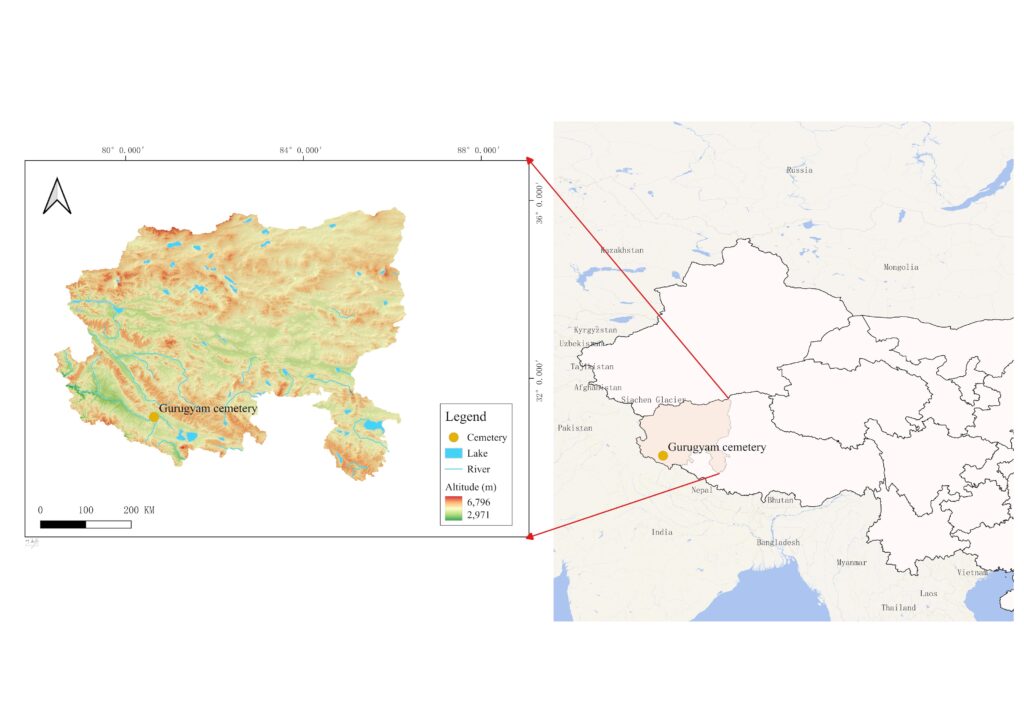

Gurugyam Cemetery sits along the upper reaches of the Xiangquan (象泉) River (Langchen Khabub གླང་ཆེན་ཁ་འབབ་) in Tibet’s Ngari (མངའ་རིས།) region. Between 2012 and 2014, archaeologists excavated 11 tombs, eight of which—including the burial known as M2—date to the 3rd and 4th centuries, roughly the end of the Han and Jin period in central China. This was a time of upheaval in the Chinese heartland. The once-mighty Han dynasty collapsed, ushering in an age of warlords and short-lived dynasties, before the Western Jin briefly reunited the realm.

The people who built and used Gurugyam Cemetery lived hundreds of miles west in a Tibetan polity, not under rule by these Chinese dynasties. But the Gurugyam society may have been described by writers living in China’s imperial centers. Ancient texts discuss a far-off “Women’s Kingdom” south of the Pamir Mountains, extending from what is now Tibet’s Ngari (Ali 阿里) region to its borders with Tajikistan and Afghanistan. The Book of Sui (隋书), compiled in the 7th century under the Sui dynasty, records that “south of the Congling Mountains lies a realm ruled by women whose rulers bore the surname Supi … they honor women and belittle men”; the Tongdian (通典), an 8th-century encyclopedic work by Du You (杜佑), offers still more detail: “In that land, women filled official posts, men acted as soldiers; women could have multiple husbands, and children took their mother’s name.”

Whether these were factual observations or imaginative projections, they outlined a strikingly different social order—one that inverted the patriarchal norms of China’s dynasties.

Could Gurugyam, and the female in M2, offer material traces of such a kingdom?

THE PUZZLE OF M2

When archaeologists began clearing the cemetery, they uncovered eight tombs sunk into the ground, each a vertical shaft lined with stones. In some they noticed flashes of cinnabar—a vivid red mineral—still clinging to the walls after over 1,000 years. Individuals buried alone were mostly on their sides with bent legs, while the bones in multi-person tombs were found shifted, in disarray.

Graves held finely woven silk, bronze vessels, ceramics, wooden objects, and iron tools. Golden funerary masks and a brocade bearing the characters for “noble” (王侯), hint at the elevated social status for some of the dead. Archaeologists also found barley grains—some alongside remnants of woven bags that once held them—and bones from cattle, sheep, and horses. Perhaps the foods were offerings or part of some other funerary ritual.

The remains within M2 belonged to a female, estimated to be between 25 and 30 years old. Though not unusually large, her tomb was meticulously constructed from three distinct types of stone. Its floor was hardened by fire, and the walls were coated in cinnabar. In addition to the human remains, the tomb also contained two complete horse skeletons, one complete sheep, and a scatter of other animal bones.

In excavation layers above M2, archaeologists found a pit packed with sheep bones—placement that suggests people came with offerings to remember or venerate the deceased after her death.

Although M2’s lavish design seems to confirm its occupant’s importance, her elite status was not immediately clear. By the time the archaeologists excavated M2 in 2014, its female skeleton was broken and incomplete. Though looting in the modern era probably caused the damage, some archaeologists saw the scene and had other thoughts: They wondered whether she was not the tomb’s master but a sacrificed attendant.

Yet multiple lines of evidence contradict this view.

RECONSTRUCTING A LIFE

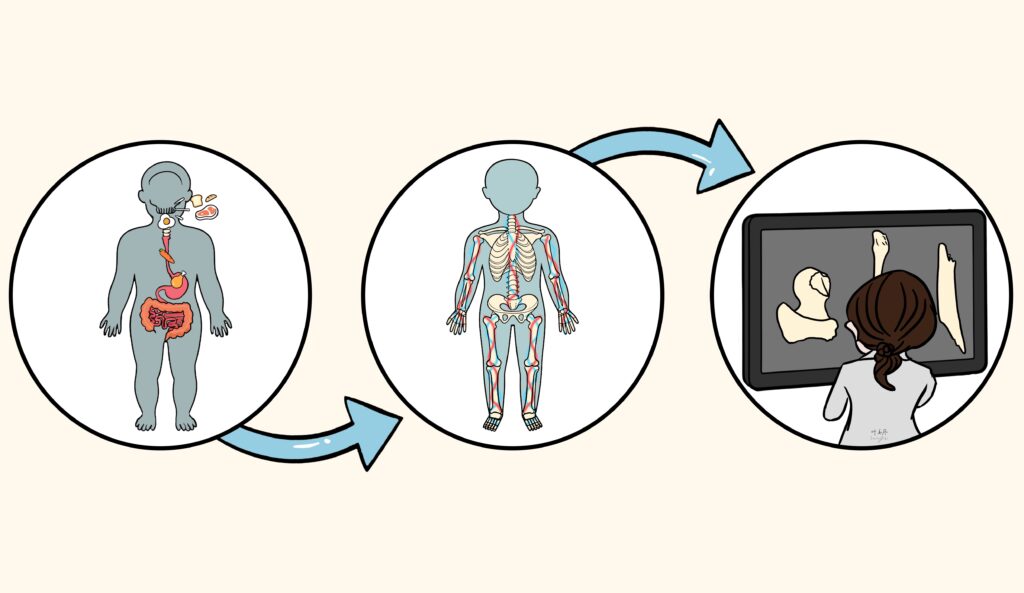

Archaeologists working at Gurugyam noted that M2’s vault was the largest and most elaborate tomb. Ancient DNA analyses reported in 2020 revealed the person inside shared close kinship ties with other individuals buried at Gurugyam, confirming the place as a family cemetery.

The timing and location of her burial seem to fit the region and era described in Chinese chronicles of a Women’s Kingdom. The earliest clear written reference to a “Women’s Kingdom” appears in the mid-5th century, when it was listed among exotic goods exchanged in diplomatic contacts.

The chronicles speak of salt-rich valleys where caravans wound their way across the mountains through the Women’s Kingdom. Perhaps a depiction of these salt traders, rock art on the plateau shows lines of figures stooped under heavy loads. The salt routes overlapped with Silk Road branches, encounters that would have brought silk, tea, and other goods into the highlands.

Foods from afar likely fed the M2 individual, based on analyses on chemical signatures embedded in her bones. A 2023 study of stable isotopes—atoms of the same element that differ in weight—revealed her bones harbored an unusually high ratio for carbon and low ratio for nitrogen. This combination points to a diet rich in plants like millet and sorghum—crops that do not thrive at high altitudes—and suggests her food likely arrived through long-distance trade. Compared with others buried nearby, her meals were more varied and higher quality, a testament to her elevated social status.

Yet privilege did not spare her from physical hardship. Her dental remains exhibit a catalog of chronic conditions: periodontitis, an infection of the gums and jaw that loosens teeth; periapical abscesses, painful pockets of pus at the root tips; severe tooth wear, with enamel ground down by coarse, gritty foods; and thick dental calculus, hardened plaque that fuels inflammation. Microscopic defects in her first molar enamel show a growth arrest around 15 months of age—a telltale sign of early childhood malnutrition or illness.

In the end, she did not live past her mid-20s, her body carrying imprints of both privilege and hardship.

RETHINKING POWER AND MEMORY

The simplest explanation remains that she was the tomb’s owner—its centerpiece, not sacrificed support staff. To me, the real mystery lies in the biases of some archaeologists, shaped for generations by male-dominated narratives that omit women from positions of power.

At Gurugyam, the M2 tomb counters these dominant histories. Her tomb and offerings, her cracked and tartar-caked teeth, DNA and isotopes embedded in her scattered bones—these lines of evidence tell a female who experienced privilege and pain. That she also held power can be gleaned from reality woven into myths.

She was not a protagonist in the grand chronicles written by scribes of ancient empires. If she appeared, it was only as a passing line at the margins of memory.

Today, aside from archaeologists studying ancient Tibet, almost no one has heard of her. I may never prove the person in M2 ruled a kingdom. But by telling her story, I hope to bring her out of the footnotes and into the public eye.