Where a River of Life Became a Border of Control

The floor of the El Paso International Airport’s baggage claim area is a marble mosaic design; blue stones represent the Rio Grande (or Río Bravo, as it is called in Mexico), and brown stones symbolize the Chihuahuan Desert. Embedded within the river and the desert are circular bronze plaques with quotes from average citizens explaining what they love about their city.

I love that El Paso has the dual culture of two countries. — Amy

The wafting scent of the desert sands after a brief but welcome summer rain, it is the smell of home. — Manny

I love the sunsets, the music, the beautiful women, the big families, and Chico’s Tacos. — Darren

As I drive from the airport into downtown El Paso, the sun is setting and its low orange rays cast everything—even the broad swaths of industrial infrastructure that sit like a no man’s land between El Paso and Ciudad Juárez—in a luminous golden glow. I look to my left, south, toward Mexico. The desert wind rolls over my arm resting in the open window. The low buildings of Juárez rush past.

I am new to the U.S.-Mexico border. I’m here from Oakland, California, to make a film and do anthropological research, so my eyes are unaccustomed to this light, this place. And as an outsider looking in, I am struck by many things, things that for people who live here have become the new normal, or more accurately, the new strange: a fortified 18-foot-high steel wall that runs between the sister cities of El Paso and Juárez, the Border Patrol jeeps—white with forest green stripes—driving alongside the wall at top speed, the agents who grill people at the port of entry, the long lines of idling cars and idling people waiting to cross the border. But the thing that strikes me most is still, quiet.

It’s the hollowed-out shell of the Rio Grande.

The three border-crossing bridges that connect El Paso to Juárez span the ghost-river’s width. Technically, the Rio Grande “runs” below these bridges, but it has been replaced by a concrete channel, with a stagnant line of brown dirty water sitting in its center.

This husk of a river takes hold and doesn’t let go. It makes me ask: How did a fertile, flowing river become an ugly concrete mass? How was it transformed into a violent border? And how did this river-border become a site of control?

One hot summer evening I drive up winding Scenic Drive into the desert hills above El Paso. Families, couples, and groups of teenagers have gathered to watch the sunset. A desert lightning storm is putting on an electric show in the distant violet sky across the border. Everyone is speaking Spanish. An ice cream truck, its generator humming, sells Mexican snacks, horchata (a sweet, creamy drink), and Jamaica juice in plastic vats. Teenagers pose for pictures, the flashes of their iPhones lighting up the darkening sky, and small children run around giggling and sending shrieks into the purple dusky night.

From atop these desert hills, El Paso and Juárez look like one merged, sparkling city. It is only when a woman points out two curving lines of white lights running in tandem, lines that hug the Rio Grande’s banks, that the border suddenly appears. Like one of those Magic Eye optical illusions, you look and look, and then bam, from nothing, something.

The story of the river-as-border begins with a war.

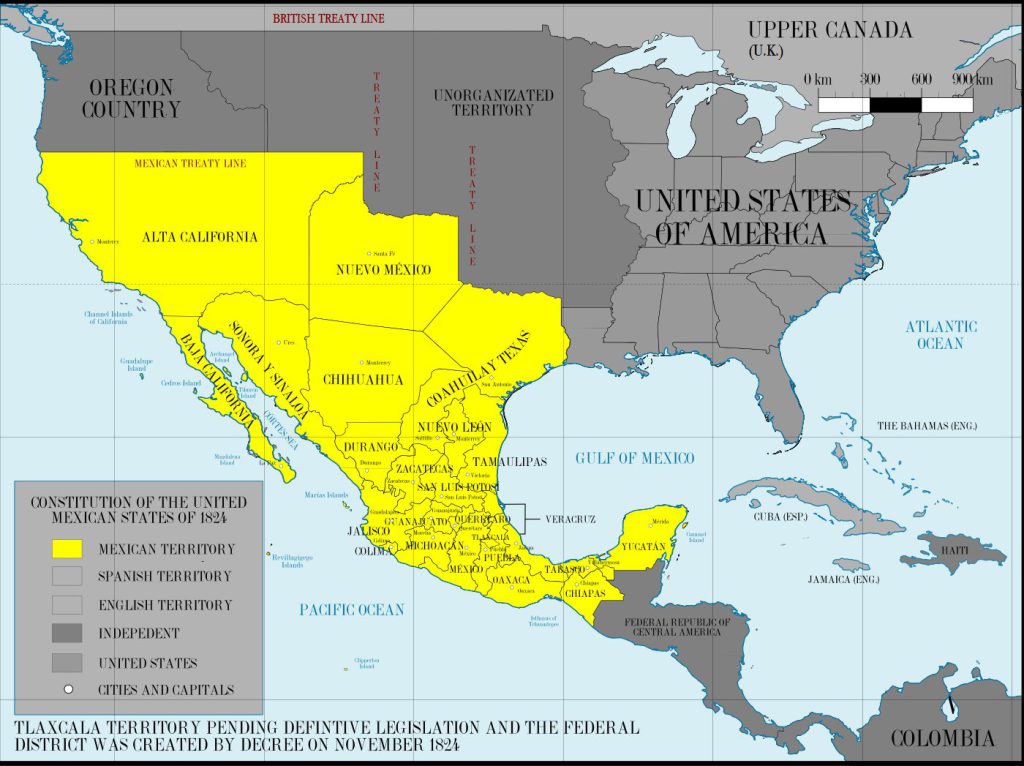

In 1845, as part of an expansionist and pro-slavery plan, the United States Congress passed a joint resolution to annex Texas. Soon after, the U.S. began to install troops along the new Texas-Mexico border into a disputed zone bounded by the Rio Grande, an area that both countries had previously recognized as part of Mexico. The Mexican government viewed the buildup of U.S. troops along this unrecognized border as an invasion of its territory and mounted an attack in 1846. With that, the United States declared war, and the Mexican-American War began. It ended in 1848, with both countries signing the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and Mexico ceding over half of its land to the United States, including all of present-day California, Nevada, and Utah, and most of Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, Wyoming, and New Mexico. The uneven circumstances of the treaty lend a certain irony to its being called the Treaty of Peace, Friendship, Limits, and Settlement Between the United States of America and the Mexican Republic. As for the Rio Grande, the treaty declared that the border between the two nations would run “up the middle of that river, following the deepest channel.”

But the river was a moving thing. The river naturally snaked and shifted. So at a boundary convention in 1884 organized by the two countries, U.S. officials set out specific principles to hold the border in place.

Any other change, wrought by the force of the current … shall produce no change in the dividing line … the line then fixed shall continue to follow the middle of the original channel bed, even though this should become wholly dry.

Twenty-one years later, at a 1905 boundary convention, it was noted that due to natural erosion, the “river abandons its old channel”; yet it was determined that the border would “remain subject to the dominion and jurisdiction” of the old 1884 convention. There was even a provision to place border markers in the abandoned riverbed.

The river-border would not be allowed to shift.

But the people in power aimed to control much more than the placement of the border.

Systematic control of the Rio Grande by the U.S. helped engender a border, but it also served another purpose: large-scale irrigation. In Rivers of Empire, an analysis of 19th- and early 20th-century water control in the American West, Donald Worster writes, “How much water is available to spread around? Where is the best location for a dam? … What should be the gradient of a canal? Those who knew the answers would determine who got the profit from dominating nature.” The U.S., it seems, knew the answers.

U.S. control of water flow into Mexico has led to a massively decreased flow of water from El Paso into Ciudad Juárez for over 100 years. As early as 1890, there were reports of a dried-up Rio Grande in Juárez. That year, the director of the U.S. Geological Survey, John Wesley Powell, testified before the U.S. Senate, saying that the people of the Republic of Mexico had no water. “The sand was blowing across the channel of the river,” he said, reporting back on his survey, “and instead of the space being covered by waves of water it was … filled with sand dunes.”

For nearly a century, the U.S. and Mexico fought over the location of the border between El Paso and Juárez. The controversy was finally settled in 1963 by an action that literally stopped the river in its tracks—4.4 miles of the Rio Grande were lined with concrete. The river’s path between the two cities was fixed, its water now diverted into narrow irrigation canals and bound for industrial agricultural fields in the deserts of western Texas. These canals sit neatly on the U.S. side of the border. And while the Rio Grande used to flow freely all the way from the snowy mountains of Colorado to the Gulf of Mexico, due to dams and levees and canals, it now struggles to reach the Gulf. For a few years in the early 2000s, the river failed to reach the coast at all. There was no river left, and the only thing separating the U.S. from Mexico was a swath of sand.

Besides forcing the desert to bloom, the irrigation canals and the concrete channel of the Rio Grande also act in other violent ways. In the first seven months of 2017 alone, according to the U.N.’s International Organization on Migration, at least 57 people drowned crossing the high-speed waters.

The river that became the border between Texas and Mexico used to have a life of its own, of course. Stories of the river’s past linger in the memories of older residents of this region.

“When I grew up in the lower valley two blocks from the river,” says Conrad, a middle-aged Mexican-American man, “it was all cottonwood trees and cotton fields. Now it’s all gone, built up and developed. They’ve built the wall and you can’t even go to the river.”

“Growing up here 50 years ago or so,” says Susan, a white woman in her 60s, “things were different. We would be playing on the banks of the Rio Grande, and it would flood its banks and change course. Suddenly you wouldn’t know what country you were in. You know, the border would cross you.”

The legacy of U.S. control was made explicit between 2005 and 2008 when, in order to clear the way for increased militarization and the construction of a new border wall, the Department of Homeland Security suspended dozens of federal environmental laws along the U.S.-Mexico border. To name a few: the Safe Drinking Water Act, the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, the Wilderness Act, the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, and the Clean Air Act.

The new wall arrived in El Paso in 2008: almost 4 miles of 18-foot-high steel. Eight years later, in 2016, the final touches were put on the fencing along the El Paso sector, leaving some 166 miles of steel running across the region.

This steel border wall has created a massive obstacle for wild animals of all types—birds, reptiles, large mammals, even butterflies. With their migration paths blocked, their nesting sights disturbed, or their food sources unreachable, many wild animals cannot survive. The Department of Homeland Security has made a tiny compromise: In a section of the border wall in South Texas, they have cut out holes, ostensibly to let large animals, like bobcats, through. But the holes are too small for these animals. The gesture, it seems, was purely symbolic.

On a very basic level, the border wall does not differentiate between species. It makes no room for the survival of animals or people.

As anthropologist Jason De León writes in his book The Land of Open Graves, the wall has pushed most migrants away from urban areas like El Paso and into deadly unwalled places, like the Sonoran Desert where, between 2000 and 2014, the bodies of 2,721 migrants were discovered in southern Arizona. Dehydration is the number one cause of death for migrants in the region. The U.S. federal government, as De León writes, has turned the desert into “a massive open grave.”

Despite the steel border wall, however, some undocumented migrants still try to cross into El Paso and its surroundings. Although it’s an urban area, and less treacherous than the Sonoran Desert, migrants still have to cross through the desert mountains that abut the border next to El Paso.

And the summer is the most dangerous time to make this crossing. “This is what we call ‘death weather,’” says Josiah Heyman, a professor of border studies at the University of Texas, El Paso. We are sitting in his air-conditioned office. It is 100 degrees out and climbing.

When you look toward Mexico from a desert hillside in the Franklin Mountains of El Paso, the landscape is so stark it seems two-dimensional—sharp tan mountains, perfect blue sky, heat. It’s easy to spot the bare mountain with a white cross on its peak.

“That’s Cristo Rey,” my friend and immigrant advocate Marisa Sieck tells me. “That’s the main place where migrants try and cross.” As she says this, two Border Patrol helicopters rise up from behind the mountain and start circling slowly. It seems that her words conjured them. The desert is still, and I am sweating. Anything, or anyone, that is moving out here will be noticed. After a few minutes, the helicopters stop circling and fly directly toward us.

They hover over us in suspended animation.

“I crossed at night over Cristo Rey,” says Daniel. [1] [1] A pseudonym has been used in this case to protect this person’s identity. We are sitting on a bench outside of a shelter for undocumented migrants. Daniel is 19 years old and is all smiles. He has a thick green cast on his right leg that stretches from his thigh to his toes. “I got to the wall and climbed it,” he says, “but I fell off on the U.S. side. I crawled for I don’t know how long, and then a nice woman in a truck picked me up and brought me here.” I ask him who he crossed with. “I crossed alone,” Daniel says. I look at him and imagine him crawling alone in the dark desert. I try not to cry.

Broken legs, broken hips, torn palms. People are still willing to climb.

Most people, however, cross the U.S.-Mexico border legally. In total, along the whole border, a million people stream across every day, in both directions. They cross for the same reasons people anywhere go anywhere—to shop, to eat at a restaurant, to attend university, to visit family. Entering into Juárez, pedestrians pay 50 cents and walk through a turnstile. Entering into El Paso, people are subject to long lines, interrogation, and harassment. This border policing has a clear target: Mexicans and Mexican-Americans. In other words, brown-skinned people. Multiple racial profiling claims are filed against border agents each year. Cars idle for hours, four lanes across, and pedestrians stand and wait indefinitely in line, filling up the space on the Mexican side of the border. A controlled flow of cars and people trickles out onto the U.S. side. I imagine that from a bird’s-eye view this crossing looks like a river of cars and people, a dam of a Customs and Border Protection station, and a reservoir of bodies.

At the ports of entry into El Paso, people crossing for a class at the university, on their commute home from work, or to shop at Walmart, stand in line next to those who come from El Salvador, Honduras, or Guatemala, who cross dehydrated, with nothing in their hands, to claim asylum.

I am standing in the line for U.S. citizens. One at a time, people present themselves to the agents, hand over their meticulously collected papers or passports or visas, and answer questions, and then they are let through. Suddenly, the line to my left stops. A man with no belongings and bloodshot eyes is getting harangued by two Customs and Border Protection officers. The man is silent and appears to be confused. His clothing is worn. There are a couple of hundred people in line around him, behind him, waiting patiently for their turn to cross. We are all silent. People avert their eyes, shift their weight from one foot to the other.

The U.S. detains roughly 400,000 immigrants each year at a cost of approximately $5 million a day, or $2 billion a year. This is, to say the least, an expensive undertaking. To cut costs, the U.S. has contracted out much of this business of control to private companies. To cut their costs, rather than detaining immigrants in physical cells, these companies release tens of thousands of immigrants each year after they are outfitted with GPS ankle monitors. This process is commonly known as “catch and release,” the same phrase fishermen use. These immigrants have to plug themselves into an outlet multiple times a day to keep the monitors charged. They are monitored 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. In other words, they are living in a prison without walls.

I am sitting in the front hall of a shelter for undocumented migrants where I’m volunteering when a Border Patrol agent and a woman who works for the Department of Homeland Security appear unannounced. They are here to serve papers to two teenage sisters from Guatemala. The sisters hadn’t been processed properly when they were detained at the border. The officer looks askance at me and says simply, “They didn’t get served.”

Earlier in the day, I had helped these same sisters choose shirts, pants, and shoes from a big room of donated clothing. They were beautiful and quiet. They spoke to each other in an Indigenous language, but mostly they spoke with their eyes. Sebastiana and Isabella. They were both wearing ankle monitors.

So now Border Patrol has come with its court papers, and I’m sitting in the hall on a metal folding chair. The officer in his green uniform, a wedding ring, and guns on his waist. The woman in tight white pants, high heels, and lots of makeup. The three of us in this hallway waiting for the sisters to be summoned. The woman fiddles with her clipboard.

When the sisters appear at the end of the hallway, the woman says yes, that’s them. The sisters have just showered and are wearing the clothes they picked out. One teen has on a Snoopy T-shirt and a pair of skinny jeans, the other young woman a white hoodie and black shorts. They both have wet hair.

The sisters stand tightly against the wall, one body with two heads. The woman takes out a small circular plastic pad. It looks like a small makeup case, an eye shadow case perhaps, but when she takes the index finger of each sister and presses it into the case, I realize what it is. She takes their fingerprints. They have to sign their names. They sign slowly. Through all of this, the sisters are silent.

These stories of control, of ankle monitors and steel walls, of detentions and dams, converge at the concrete riverbed.

Once a year, immigrant advocates from the Border Network for Human Rights, an organization based in El Paso, organize Hugs Not Walls, an event that allows hundreds of families who are separated by their immigration status to reunite in the middle of the concrete riverbed under Border Patrol supervision. Videos on YouTube, posted by family members who have participated in these events and local and national TV stations, show families shrieking and crying for joy as they run toward one other through the sandy muck of the riverbed. Elderly parents hug their adult children for the first time in decades, young kids meet a mother or father for the first time. There are sobbing hugs and face caresses and rushed exchanges of love. The families have four minutes together. Then their time is up.

The violence of the border—its function to separate, to divide, to control—creates the perfect conditions for these extreme and desperate reunions. Put another way, the bedrock of these scenes of connection and joy is the suffering that necessitated them in the first place: The river that became a border, more than 130 years of control, the slow but steady damming of water, animals, birds, people. This is how we have arrived at a situation where families have four minutes together, standing in the muck of a concrete culvert.

Back at the El Paso airport, heading home, I pass by the marble river mosaic on my way to the security line. The blue stones for water, the brown stones for desert, the bronze plaques for people.

I arrive at security. In every lane, alongside a standard TSA official, stands a Border Patrol officer, stopping people and checking IDs. Ahead of me in line, a woman with thick black hair holds an infant wrapped in a bright pink fleece blanket. On the mother’s leg is a gray rubber ankle monitor.

There is no wall in the airport, no dam, no canal, but the border is still here, flowing out in the form of border police, of checkpoints, of ankle monitors. The border, in other words, has overflowed its banks. Because unlike people, or wild animals, or water, the body that remains uncontrolled in this region—the body that is allowed to flow and spread—is the border itself.

The border is wide in this place. It fans out for miles, out from the ghost-river and onto people’s bodies, out from the steel wall and into the desert’s wild things, out from the dotted line on a map and into the airports, the families, the mothers. Here, the border is also on the inside.