Corporate “Sorcerers” Reveal the Magical Power of Capitalism

To Indigenous Marind communities living in West Papua, Indonesia, the year 2015 was abu-abu—“gray” and “uncertain.” Forests set ablaze to clear land for oil palm and pulpwood concessions filled the sky with a suffocating haze. Vegetation was bulldozed and waterways were diverted to irrigate the plantations, leaving the landscape brown and desiccated. Hundreds of dead fish floated on stagnant ponds while other riverine critters choked on pesticides, chemicals, and sludge.

The widespread destruction was exacerbated by an extreme El Niño, contributing to the longest drought in two decades. In the villages of the Merauke district, where I conducted 18 months of ethnographic fieldwork between 2013 and 2018, Marind people gathered every morning at dawn to recite incantations in the hope of summoning rain. None came.

In December 2015, representatives from an Indonesian oil palm company visited the village and offered to hold a rainmaking ritual. Most villagers assumed the proposal was a ruse. This corporation had repeatedly urged the villagers to cede their lands for an oil palm project, and the businesspeople were becoming increasingly desperate to start development or risk losing their permit.

Many community members said the ceremony would be co-opted and fake, and therefore doomed to fail. These businesspeople from Java were ignorant of Marind customs, myth, and ritual codes, so they would be incapable of manipulating the elements, organisms, and spirits whose collaboration is necessary for rituals to succeed.

Nevertheless, the company insisted on holding the ceremony—and, in doing so, may have permanently destroyed the community’s relationship with their rain-making tradition.

Only a handful of villagers attended the ritual, largely out of fear of reprisals from the company and the government if they did not comply. Those who did attend were struck by how closely it followed secret Marind traditions.

The corporate hosts wore elaborate bird-of-paradise headdresses, handwoven sago-frond skirts, and ornaments fashioned from the feathers and bones of cassowaries and boars. They brought the necessary food offerings—betel nut, sugarcane stalks, sago, and bananas. Although their pronunciation was flawed, the officiants read handwritten Marind spells with great solemnity. The dances, chants, and sacrifice of a fattened male pig took place just as Marind etiquette required.

As the ceremony unfolded, Pius, an elder renowned for his extensive knowledge of Marind myth and ritual, suddenly grabbed my shoulder. [1] [1] All names except the author’s have been changed to protect people’s privacy. He pointed with astonishment at the horizon, where thick clusters of dark clouds were gathering. Thunder reverberated between the ritual drumbeats and the dancers’ chanting and stamping. At the apogee of the final rain dance, the clouds burst above the village, releasing a heavy downfall that lasted more than two weeks.

In the aftermath, the villagers offered several explanations for this unexpected outcome. Some suggested the company had checked the forecast and timed the event to coincide with predicted rainfall. Others suspected fellow villagers of divulging traditional spells to the company in exchange for money and alcohol. Some said it was coincidence or luck.

For the vast majority of my interlocutors, however, the success of the ritual confirmed widespread rumors that foreign corporations are actually powerful and lethal sorcerers. And given corporations’ abilities to transform natural environments and human societies across the world, it’s a perspective worth considering.

According to Marind, sorcerers are people (mostly men) who collude with evil forces lurking in the forests in order to further their personal interests and material gains. Sorcerers tend to be highly individualistic power-seekers who use their supernatural abilities in clandestine ways to inflict suffering upon vulnerable people. These characterizations of sorcerers echo the beliefs of people across Melanesia.

As Viktor, a village elder, explained, foreign oil palm corporations wield this kind of diabolical power to wreak havoc on Indigenous peoples and their lands. They obliterate the forest, undermine Marind people’s ancestral relations to kindred forest organisms, and pursue a seemingly insatiable hunger for resources, profit, and power.

Marcelina, a Marind mother of three, said companies are always greedy for more land, just like sorcerers are said to be perpetually hungry for the flesh and blood of their victims. Geronimo, a young Marind man, spoke of corporations draining the flesh and fluids of Marind and their plant and animal kin by transforming diverse forests into homogeneous plantations and diverting waterways for irrigation.

Like sorcerers who lure their victims by appearing as normal humans, corporations are also profoundly deceptive, according to many Marind community members with whom I have worked over the last seven years. They entice villagers with promises of jobs, money, and better futures that rarely materialize. They cause clans previously bound by shared pasts and kinship to fight over compensation and land rights.

Corporate sorcerers, Elder Petrarchus explained, are also magical in the way they replicate themselves and exist in several places at once. Their plantations proliferate across space under dozens of different names and logos. Their powers are spread over the many levels and individuals who make up corporate entities.

Just as sorcerers operate in mysterious ways and cannot be easily identified, corporations govern their concessions from a distance—Jayapura, Jakarta, Singapore. Their authority is everywhere, even as their agents remain elusive.

There is something magical about the power of multinational corporations and their tentacle-like supply chains.

Since corporate sorcery originates from foreign places, its techniques, instruments, and remedies are unknown to Marind. As Serafina, a mother of four from Merauke, put it: “Sorcery is like oil palm. We do not know where it comes from or how to stop it from spreading. In both cases, we cannot escape the destruction and suffering.”

From the perspective of Marind community members, corporate sorcerers’ supernatural powers are heightened by their association with other threats. Corporate interests are protected by the Indonesian military, whose deadly operations are often described as sorcery by Papuan peoples. These businesses also attract a growing influx of non-Papuan migrants, who are said by Marind to harness new and foreign spells, rituals, concoctions, and objects in order to appropriate land, obtain jobs, and enrich themselves at the expense of local Papuan communities.

Modern capitalism’s utilitarian focus on profit may seem far removed from sorcery. Capitalism, as sociologist Max Weber argued, is driven by an extractive ethos that strips the world of its supernatural dimensions.

Yet there is something uncannily magical about the power of multinational corporations and their tentacle-like supply chains. Some mega-companies are so widespread they seem to have achieved omnipresence. Their success stories are infused with mythology and spirituality. Like a powerful, destructive sorcerer, capitalism is arguably the primary force behind ecological degradation and climate change.

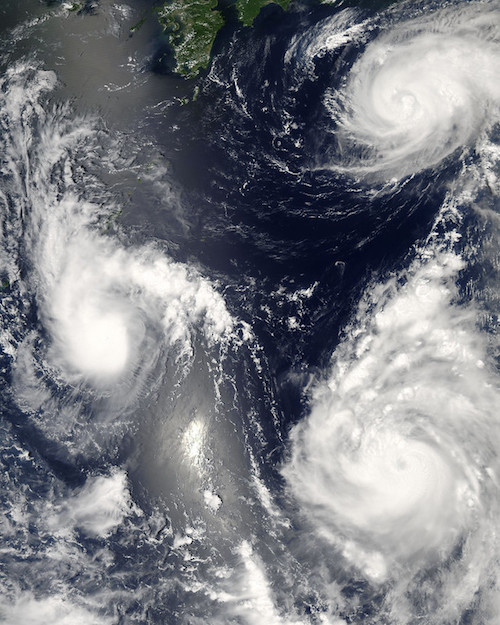

Thus, Marind villagers’ characterization of corporations as sorcerers invites people to take seriously the idea that modern capitalism is a kind of magic. It is a powerful force that can sow conflict between communities, profoundly alter landscapes, and even conjure rain, hurricanes, and drought through global warming.

Of greatest concern to many of my companions is the fact that corporations’ “supernatural powers” seem far greater than those of Marind sorcerers. When the corporate rain-making ceremony appeared to succeed, it sent a message to the villagers that their own failed rituals were impotent. Moreover, it emphasized the community’s powerlessness in the face of broader issues—their loss of land, resources, and autonomy.

The Indonesian government denies West Papuans their right to political and cultural self-determination. Politicians promote agribusiness projects that are routinely implemented without the free, prior, and informed consent of Indigenous landowners, in violation of several international human rights laws that Indonesia has either signed or ratified. And these ventures contribute to the growing marginalization of Indigenous Papuans in some regions of the province where settlers now represent more than 60 percent of the population.

Several weeks after the co-opted ritual, the Khalaoyam community decided they would no longer perform or participate in rainmaking ceremonies. “Rather than let the companies manipulate our Indigenous rituals, it’s better that we stop practicing them altogether,” explained Pius.

The costs of abandoning the rainmaking ritual have been high. Social relations across clans that were once sustained through this collective ceremony have weakened. Many Marind told me that elders were no longer teaching rainmaking—or other ritual spells and dances—to the youth. This knowledge is therefore likely to be lost within the next generation.

Most worryingly, the success of the corporate ritual did play a part in convincing some community members to surrender their lands. When I last visited in June 2019, I found widespread disagreement among villagers over whether they should abolish other Marind rituals that corporations might manipulate.

The co-optation was not an isolated incident. In several Papuan villages, corporations have held co-opted pig sacrifice ceremonies and ritual healings, expecting villagers to reciprocate by ceding their lands.

Rituals, as anthropologists have demonstrated, can play a critical role in affirming and sustaining the social order and in providing psychosocial relief to their participants. But rituals that succeed in the “wrong hands” can be deeply problematic.

Corporations’ exploitative use of spiritual traditions represents the rise of a new order ever more deeply shaped by greed and opportunism. This order is far from just economic in its form and impact. Rather, the destructive effects of capitalist “sorcery” ripple across multiple realms—the human, the elemental, the natural, and perhaps even the supernatural.