The Making of a Wrinkle Convert

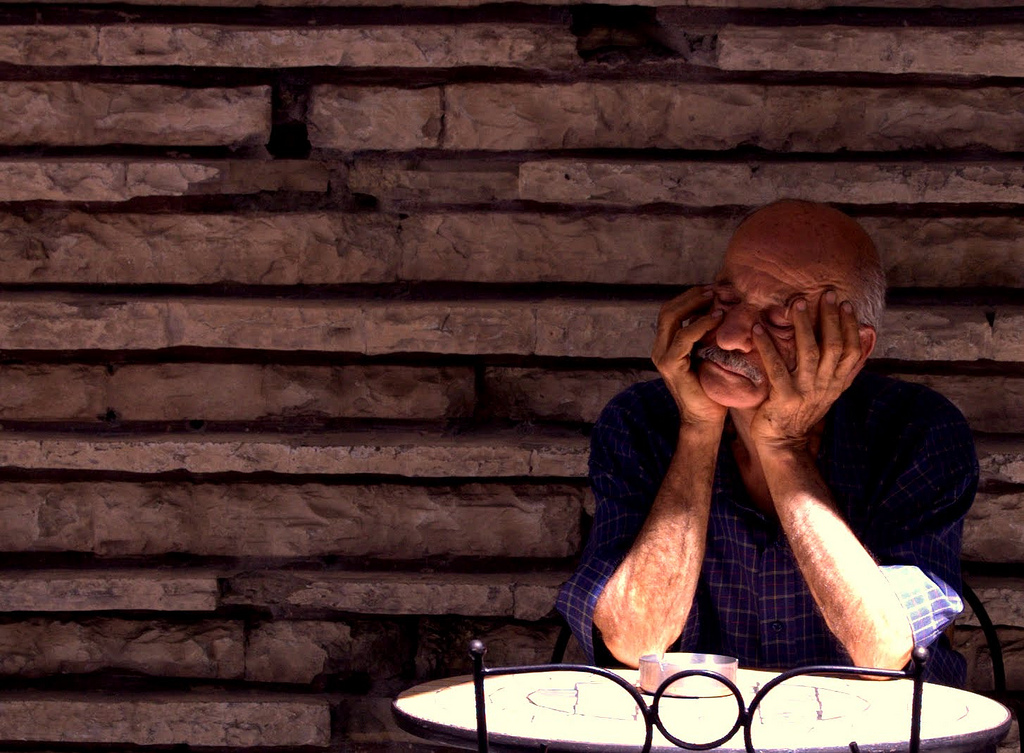

I have had a wrinkle epiphany, prompted by a chance meeting with a stranger, a senior scholar whose face generously showed her age. She was a model of insight and poise as she spoke. She owned her wrinkles. I started paying more attention to older faces around me and thinking about the meanings of our facades.

I am now officially for wrinkles. Wrinkles have gotten a bad rap for a long time, and that’s a shame. Wrinkled faces should be associated with experience, wisdom, and engaging stories. Instead, they’re major signals of being ancient, out of touch, and irrelevant in our youth-dominated consumer society. The most visible signs of aging are seen as a handicap, a source of bias. I protest this! Yet, there’s more to this problem than meets the (wrinkle-free) eye.

Wrinkles have been around as long as humans have been relatively hairless ex-apes living modestly long lives. Early Homo sapiens or Homo neanderthalensis who were well-aged showed their wrinkles with confidence. (I know this from all the artists’ reconstructions of our ancestors.) Being a mature human has always meant being wrinkled.

Wrinkle Accumulation

Wrinkles are the natural order of things. Youthful, elastic skin stretches and slumps over time. Already the biggest organ of the human body, skin becomes larger. Wrinkles embody entropy.

What causes wrinkles? Gravity, for one, is a serious offender. Aging skin meets gravity, which results in sags—or wrinkles made large. Faces droop. Butts fall. Brows crease. Breasts loll. Necks wattle. Crow’s feet and jowls emerge.

Sun exposure accelerates wrinkles, a special irony for light-skinned people who think a tan is evidence of health. Expressiveness amplifies wrinkles. Smiling, laughing, crying, and frowning—signs of emotional engagement—all contribute. Our skin reflects years of exposure to both the outdoors and social quarters. That should not be held against us.

Our stigmatization of wrinkles is disturbing. Once I reached retirement age, I embodied and reaffirmed such judgment every time I looked in the bathroom mirror and wondered how I could conceal the latest lines on my face. But now, I pledge to reframe this view as crazy—or at least mindlessly superficial. Wrinkles express individuality and maturity; hostility to them scorns the benefits of experience and age. We should not let them undermine our sense of self. The late American essayist Nora Ephron should never have been driven to write the essay “I Feel Bad About My Neck.” In accepting my own wrinkled skin, I can see that prevailing attitudes have given rise to an entire anti-wrinkle cultural-industrial complex. It’s a vicious cycle. We see wrinkles as bad, a sign of decrepitude. This launches a need for products and commercially available fixes, which makes the prevailing view even more entrenched and inescapable. We can do better.

Wrinkles don’t just happen to faces. Clothes rumple and crease. Natural fibers like cotton and linen wrinkle badly. Synthetic fibers don’t. This fact might lead us to see wrinkles as natural and the state of being unwrinkled as artificial. And yet our culture has embraced unnatural fibers wholeheartedly. They give us the illusion of control.

Wrinkle Acculturation

Wrinkled clothes are important social markers. It’s considered okay to be casual but not wrinkled. The homeless have wrinkles—so do druggies, alcoholics, and hippies. Wrinkles are aberrations and signal character flaws, or so we’ve been taught. Most Americans think the fewer the wrinkles, the better.

Corporate personnel, politicians, and culture heroes—fictional and real—are unwrinkled. Businesspeople view suit wrinkles as being in the same realm as mustard or ketchup stains. No respectable character in Don Draper’s advertising world of Mad Men, or in Alicia Florrick’s legal world of The Good Wife, is wrinkled. Collectively, the superheroes are as unwrinkled as they could possibly be.

The most successful people are wrinkle-free and trustworthy. Straight arrow. Straight talk. Straight shooter. Straight-laced. Being straight. Sit up straight. “Straighten Up and Fly Right.”

Wrinkled is a metaphor for situations that don’t go smoothly. People say, “Their plans were wrinkled by the missed flight.” “There’s a new wrinkle in our business forecast.” “We try to straighten those problems out.” During his candidacy, Donald Trump exploited “crooked,” which is wrinkled on steroids, in labeling his opponent “Crooked Hillary.” The “straight and narrow” is the metaphorical high road, what is socially and politically acceptable. Wrinkled and crooked are not.

We live in an anti-wrinkle age, reinforced by all the powers of consumer society. We are cultural products of a consumer-dominated, image-is-everything world. We allow wrinkles to be used against us, as if they were displays of slovenliness or deviance, or of looming demise.

The Anti-Wrinkle Campaign

Advances in technology have only encouraged the prejudice against wrinkles. For any wrinkles on clothing, there are products, services, and procedures to remedy the dreadful situation: irons in every home and hotel room, starch, dry cleaners, wrinkle-free fabrics, dryers, and personal valet steamers to the rescue.

As for skin, cosmetic surgeons—who are predominantly male—remove or reduce wrinkles in patients, who are largely female, for whom wrinkled skin is especially unacceptable. They have performed face-lifts, forehead- and eyelid-lifts, and neck-lifts. In 2014 and 2015, doctors injected Botox and Dysport more than 13 million times, raking in around US$2.6 billion in 2015, and promoted artificial youth by slowing the wrinkling and sagging processes. Prolonged resting bitch face (RBF)—a face that, when at rest, looks angry—works against wrinkles cheaply, but it may have other outcomes, such as sexist criticism.

We reinforce the burden wrinkles impose on women with our semantic generosity toward wrinkled men. Euphemisms like “weather-beaten” and “rugged” are positive when used to describe men. I don’t know any woman who would consider “craggy” a compliment. As Jane Fonda puts it, “My pal Redford gets furrows and character lines. I get wrinkles and crow’s feet. It ain’t fair!”

Wrinkles get too much attention. In 2016, after years of research, scientists from MIT, Massachusetts General Hospital, hair care company Living Proof, and technology company Olivo Labs announced a revolutionary breakthrough of a polymer coating (XPL) that could be used to deliver medications and protect dry skin. But those qualities received far less attention than the product’s ability to mimic “the mechanical and elastic properties of healthy, youthful skin.” The long-sought fountain of youth may well be a polymer of youth.

Wrinkle Rebellion

Why do we care so much about wrinkles? If dirt is “matter out of place,” as anthropologist Mary Douglas has written, wrinkles are lines out of place, and like dirt they “offend against order.” Beyond normal aging, wrinkles challenge our cultural constructions; they represent a resistance, a rejection of “proper” appearance. Wrinkles disregard societal imperatives by marking people, clothing, or events in unique ways. In our orderly, pressured, and pressed world, we should welcome the individuality and informality associated with wrinkles. Wrinkles are like interruptions in a boring monologue, a form of rude rebellion.

To be human is to have wrinkles—on faces, in clothes, in life. Get over it. Let’s see wrinkles as opportunities to escape the straightjacket of conformity. On the practical side, embracing wrinkles would save time and money that’s too often spent on riddance. It would also lift our self-esteem.

I am a wrinkle convert. Before this transformation, I bought into cultural biases against wrinkles, but from now on I will champion wrinkles. They have worthwhile stories to tell.