India’s Third Gender Rises Again

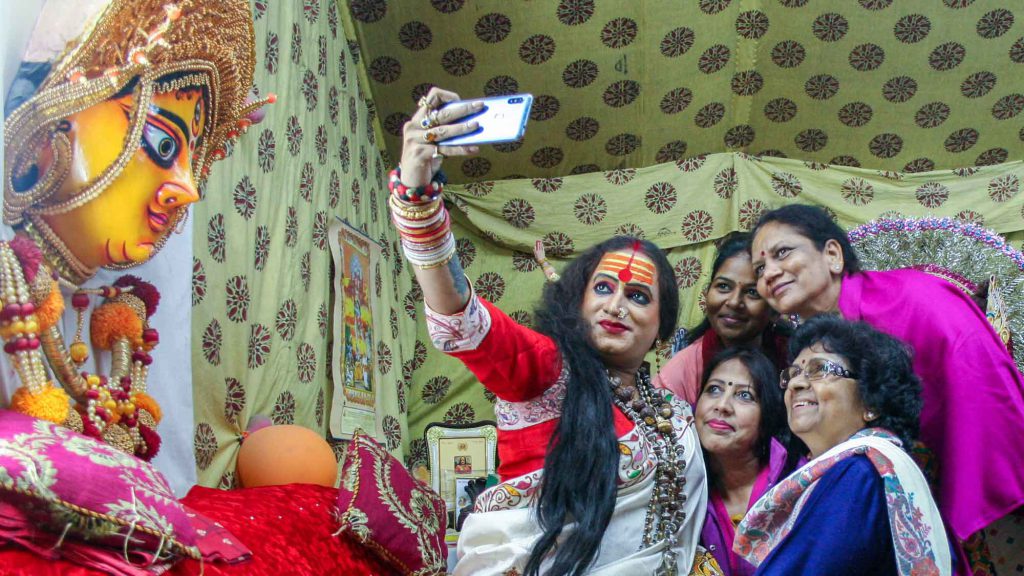

Laxmi Narayan Tripathi sat on her temporary throne like a demigoddess in a jade and scarlet sari. A line of devotees jostled to cram inside her golden cloth tent, and she joked with them, flirtatiously: “I am giving ashirwad (blessings) only, not love letters. Everyone be tension-free, and love yourself.”

The crowd giggled, then settled down and patiently awaited their turn. Some of them had come to this tent at India’s Kumbh Mela pilgrimage festival—the world’s largest gathering—to receive Tripathi’s advice on everything from loss of appetite to unemployment. Some prostrated themselves at her feet and made offerings of money, food, clothing, and jewelry. Some just wanted selfies.

She listened to each person with great interest and enthusiasm, reassuring them and telling them not to worry. When she bestowed a blessing on someone, she bit a 1 rupee coin and handed it to them along with grains of rice. In India, it is considered auspicious to be given rice and a coin bitten by a hijra—a person from a “third” gender community.

There are approximately half a million hijras and other third gender individuals in India, plus smaller numbers in Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Nepal. The hijra identity is a unique blend of biological, gendered, and sexual identities underpinned by religion and bound by a tight-knit social structure. Hijras include people assigned male at birth who may or may not undergo castration and modifications such as breast implants, as well as some (but not all) intersex people and transgender women.

Like Tripathi—the high priestess of the Kinnar Akhada convent of Hindu hijra priestesses—hijras typically dress in women’s clothing, wear makeup, and take feminine names. To identify as a hijra, as opposed to a transgender or other third gender person, an individual must be ritually adopted into the community in a process that can take months to years.

Distinct from transgender and intersex identities in other countries, hijras occupy a unique and contradictory place in Indian society. Hindu mythology deifies them, and British colonists demonized them. So today, they are revered by many as demigoddesses and reviled by others as deviant victims of bad karma. For more than a century, they were ostracized almost to the point of being forgotten.

Now, Tripathi says, “hijras are reclaiming their lost position in society through religion.” Their newfound prominence has arisen largely thanks to Tripathi, who gained fame on a reality TV show and garners followers through her savvy PR and social media team.

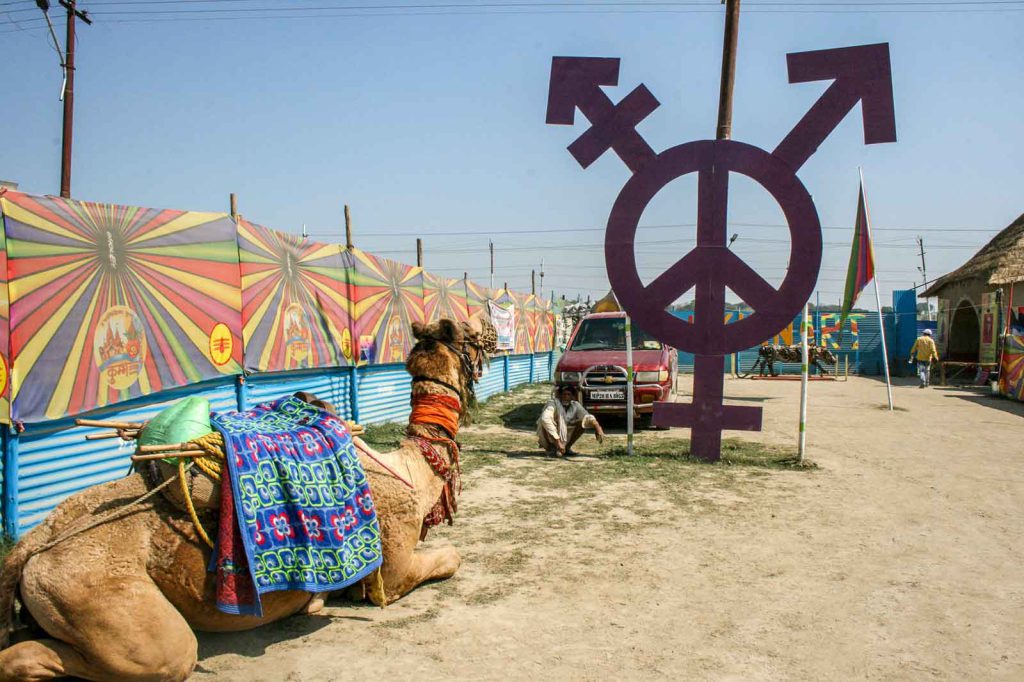

January of this year marked a turning point in the hijra community’s struggle for respect. For the first time, the Kinnar Akhada fully participated in the Kumbh Mela festival by taking the “royal holy dip.” Tripathi and her hijra followers bathed in the sacred confluence of the Ganges, Yamuna, and (historical) Saraswati rivers—a ritual traditionally reserved for Hindu priests, who are mostly male and Brahmin, or upper caste.

For the last nine years, I have worked with hijras as an anthropologist and a social worker, witnessing their struggles and successes. I learned to speak their secret language, was ritually adopted into the community by a guru, and later bequeathed with the title “honorary hijra.” I am continuing my doctoral research with this dynamic community, exploring gender and sexuality in ways that defy what textbooks teach us, and hoping to understand how the hijra subculture has survived, despite numerous attempts to eradicate it.

Hijras’ purported supernatural powers are enshrined in Hindu mythology, and their gender fluidity mirrors the androgynous gods. The god Shiva is sometimes portrayed as half-male, half-female. There are many stories in which the male deity Krishna takes the form of a woman to briefly marry a man, and the goddess Lakshmi and her husband, Vishnu, merge to form an androgynous person.

Ancient Indian texts like the Kama Sutra describe the third gender as tritiya prakriti, or “third nature,” insinuating that three genders are part of the natural order. Most famously, the 2,300-year-old Indian epic poem Ramayana tells the story of the deity Lord Rama, who is banished from his kingdom for 14 years. His subjects attempt to follow him into the forest, but he tells the “men and women” to return to their city. His hijra followers—not belonging fully to either gender—feel unbound by his order and stay. Touched by their loyalty, Lord Rama grants them the ability to bestow blessings at weddings, births, and other important occasions.

During the Muslim Mughal dynasty, which ruled much of India from the 16th to 18th centuries, hijras were often compulsorily castrated and became trusted guardians of the harems. In this time period, some hijras also enjoyed prominent positions as political and legal advisers, administrators, and generals.

Then the British arrived, foisting Victorian sexual mores on Indian culture. The colonists accused the “eunuchs” of sodomy, prostitution, and kidnapping and castrating young boys. They saw the third gender as a threat to morality and political authority. The British criminalized being a hijra under the Criminal Tribes Act of 1871, stripped hijras of their inheritance rights, and launched a campaign to erase them from public consciousness.

The hijra community was forced underground.

Since then, hijras have lived on the fringes of society. They typically earn money by asking for voluntary donations in exchange for their blessings, performing at weddings and stag parties, begging, and engaging in sex work.

Most people who become hijras come from working-class or lower socioeconomic backgrounds. As children, they are typically bullied and shunned by their families. Tripathi has said she was abused by a family member and by several men close to her. Some of her relatives conspired to kill her.

Hijras are frequently victims of hate crimes, including rape and assault, that often go unreported. One hijra broke down when she told me about the dangers she faces in her street-based sex work. Once, a police officer cornered her and sexually assaulted her, she said. She didn’t report him because she was afraid he would harm her or forbid her from working in the area again.

Seeking security from attacks and harassment, hijras formed clandestine, ghettoized communities. Members developed a complex system of kinship and social stratification requiring the patronage of a hijra guru.

“What is it that we have except our gurus?” Champa, a hijra living in Delhi, told me. [1] [1] To protect people’s privacy, all names except Laxmi Narayan Tripathi’s and the author’s are pseudonyms. “Our gurus are our saviors. They have rescued us from the harsh and brutal world. We have no one that we can trust. Even our families—the one to which we were biologically born—have disowned us.”

The guru-disciple system is no utopia. Disciples become domestic servants in exchange for room and board and other benefits, though some scholars have called this thinly disguised bonded labor. In addition, some hijras have called for an end to this system because some gurus encourage their disciples to do sex work. And though most hijras are reluctant to admit it or even speak about it, India’s caste system plays a role in hijras’ social stratification. For example, Sharmili, a hijra from near New Delhi, told me her guru does not permit her to collect ritual blessings because she was born into the lowest caste.

“This is why we hijras are considered to be godlike, as we undergo such pain that ordinary men and women cannot even think of bearing.”

In the hijras’ social stratification, going through the castration ritual garners higher respect. Tripathi has said she does not condone a hierarchy based on castration but admits there is strong peer pressure to get castrated. She got the procedure done earlier this year, but she downplays its significance, saying her soul is more important than what lies under her skirt. “I have lived my 40 years of akwapan [uncastrated]. Now I just felt like I need to be this way also,” she says. “I want to take all the sides of life.”

Traditionally, castration is believed to give hijras the power to confer fertility on couples. Many newlyweds and pregnant women seek hijras’ blessing for a healthy baby boy. It is also believed that removing the penis and testicles elevates hijras to the level of religious ascetics, since castration is equated with freedom from desire, a renunciation of pleasure, and a crucible of pain.

Because hijras are usually poor, they do not have access to expensive, advanced sex reassignment surgery. Instead, most hijras seek out their guru’s networks for castration, which is typically performed secretly and often by faith healers who are not authorized medical practitioners (although some private medical clinics in New Delhi are now doing the surgery).

Some castrated hijras develop life-threatening post-operative complications and even die. When hijras seek medical care, they have often been turned away from hospitals, in part due to the existence of male and female wards.

“This is why we hijras are considered to be godlike, as we undergo such pain that ordinary men and women cannot even think of bearing,” explained Kapila, a castrated immigrant hijra from Bangladesh. “We are the closest to the Almighty. … In the Mahabharata—the greatest Indian epic of all times—we are called Ardhanarishwar: half-(wo)man, half-god.”

The hijras’ rituals and strict internal kinship system have their downsides, but they also result in a strong sense of community. This may be what has allowed the hijra identity to survive, distinct from transgender identities in India and elsewhere.

For outsiders, the distinctions between hijras, third gender individuals, trans men and women, and other gender non-conforming people can be confusing. Many have understood third gender to mean only the hijra; however, numerous other gender nonconforming identities fall under this umbrella term—and yet, some argue against the use of the term “third” gender.

One of the main differences between trans and hijra identities is that trans people have the freedom to self-identify as trans. To identify as hijra, a person must be initiated through a lengthy adoption process based on hijra customs that are still not recognised by Indian law. The general trans population in India does not adhere to such an internal social system, but subsequently, they have a less tight-knit community than hijras. Also, conventionally, trans men are not a part of the hijra community.

But the status and visibility of all gender non-conforming people in India is changing—thanks to a landmark court decision.

In 2014, India’s Supreme Court officially recognized the third gender. The decision means the government must provide equal opportunities and legal and constitutional protection to trans people. The ruling was a result of years of effort by the LGBTQ community—including Tripathi, who was a co-petitioner in the lawsuit. To her, the ruling meant she could finally consider herself Indian because her country had once again recognized the third gender identity. Soon after, she embraced Hinduism and started the Kinnar Akhada, the first Hindu monastic order of hijras.

In another victory, India decriminalized homosexual sex in 2018, overturning a 160-year-old law instituted by the British.

Still, hijras face many hurdles. In 2016, the Indian government proposed the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Bill, which criminalized begging and denied people’s right to self-identify as trans, instead requiring them to be screened by a committee. The bill faced such opposition that those provisions were removed.

The controversial campaign fueled stereotypes about hijras as “loose” sex workers who are “confused” about their identity.

The revised bill, which passed in the parliament’s lower house in August, remains controversial. It punishes sexual assault against hijras far less harshly than sexual violence against cisgender women (women whose gender identity matches the sex they were identified as having at birth). And its vague language implies that surgery—plus approval from a medical authority and district magistrate—is required for a person to legally change their gender identity.

Hijras even face discrimination from some in the trans community. In 2016, the Transgender India Facebook page launched a campaign called “I am not a hijra.” In the series of images, people hold signs displaying messages (some of which appear to be written in photoshopped text), including “I am trans, and I am a surgeon. I am not a hijra” and “I am trans, but I am not a sex maniac. I am not a hijra.”

The campaign was denounced as classist, as it sought to disassociate trans people who “draw a six-figure salary” from hijras, who are mostly working class and uneducated. The photos and the conversation surrounding them also fueled stereotypes about hijras as “loose” sex workers who are “confused” about their identity.

Amid the campaign controversy, social media users also criticized the hijra practice of “skirt lifting.” When a person refuses to pay a hijra for their blessing, the hijra may curse them and threaten to lift their skirt and expose what lies underneath. To the person being flashed, this is often seen as harassment. To hijras, it’s seen as a way to turn the tables on discrimination—to use the public’s fascination and discomfort with hijra sexuality to claim power in a situation in which they have been disempowered.

The hijras’ efforts to reclaim their status through religion and social media have also courted controversy.

India’s increasingly right-wing political climate, which often promotes Hindu nationalism at the expense of other cultures, is exacerbating fault lines between Hindu and Muslim hijras. These tensions came to a head after Tripathi publicly supported construction of a Hindu temple dedicated to Lord Rama on a site where, in 1992, Hindus destroyed a mosque, sparking riots that killed thousands of people. Many Indian gender-nonconforming, trans, and intersex individuals condemned the Kinnar Akhada’s support for the temple, saying it fueled anti-Muslim sentiment.

These clashes highlight a dilemma facing the Kinnar Akhada: By attempting to legitimize the hijras’ status through Hindu doctrines, do they risk excluding non-Hindus and hindering the tolerance they are trying to encourage?

The Kinnar Akhada’s use of social media has also been met with mixed reactions. The group gained popularity by streaming live feeds from the Kumbh Mela on Facebook, letting YouTubers produce exclusive videos, creating exciting and colorful spaces on Instagram, and getting #transgender trending on Indian Twitter during the Kumbh. Thanks to the religious order’s PR team, headed by a journalist, images of Tripathi and other hijras from the Kinnar Akhada taking the holy dip were splashed across local and national publications.

However, the group’s instant mass appeal was seen as competition for the older religious orders. The Kumbh Mela’s organizers pushed the Kinnar Akhada to the fringes of the festival site, far from the main gathering areas. According to a researcher who conducted fieldwork at the festival, some members of traditional Akhadas deliberately pointed toward the wrong path when people asked for directions to the Kinnar Akhada—perhaps in the hope of dwindling their audience.

Still, the devotees managed to find their way to the far-flung site, with its little gold tent, for blessings and selfies with the demigoddesses. And the hijras felt empowered, if only momentarily, in their new representative space.